Before coming to Cambodia, I’d never heard of the Killing Fields.

Before coming to Cambodia, I’d never heard of the S-21 prison, or the Khmer Rouge, or the Second Indochina War, or Operation Menu, or the Cambodian Civil War.

I knew none of these things, and after hearing about them, it makes me wonder what other horrifying modern events I missed in History class.

Cambodia was the place I was most nervous to visit during my travels. I was going into the country completely blind. Malaysia and Singapore were unfamiliar, but they are further industrialized, easy to get around, English-friendly. I wasn’t sure how much of that to expect here.

These fears proved to be unfounded, as I quickly adapted to life traveling via tuk-tuk. USD is an accepted form of currency, and the cities have exploded with growth in the last ten years. I mean, they even have a Hard Rock Cafe.

What I was not prepared for, was the dark and recent history of Cambodia. I got a ride in a tuk-tuk from the airport to my hostel, which was blasting so loud that I could hear the music 2 blocks away. Note to self – a hostel called ‘Mad Monkey’ is the place to stay if you want to be wasted at 2 pm and spend your nights sleeping by the pool. It is NOT the place to stay if you are looking for a peaceful night’s sleep after a day of sightseeing. Consider my lesson learned.

My driver came the following morning to escort me around the city, though I wasn’t prepared for the grim sights that awaited me.

The Killing Fields are mass graves around Cambodia thought to hold at least 1,386,734 bodies, victims of the state-sponsored genocide from 1975-1979 under the leadership of General Secretary Pol Pot. If you include people who died from disease and starvation, that number rises to closer to 2.5 million. That is out of a total population of 8 million – more than 25% percent of the population died during this conflict over the course of 5 years. My day started at Choeung Ek, the most famous of the Killing Fields.

The Cambodian Civil War of 1970-1975 was complicated and is what eventually allowed the Khmer Rouge to take power. The US bombing of Cambodia contributed to the Khmer Rouge eventually seizing power.

There seemed to be little distinction of who could be targeted by the Khmer Rouge, with men, women, and children all victims. Some things that qualified you as an enemy of the state were wearing glasses, being considered an ‘intellectual’, speaking two or more languages, living or having lived abroad, Buddhist monks, foreigners—the list goes on and on. The government even sent letters to known ex-pats living overseas and asked them to come home in order to help get their country back on track. Those who did return, thinking themselves patriots, were promptly sent to prison or murdered.

If you’re squeamish, consider this a trigger warning and skip this next paragraph.

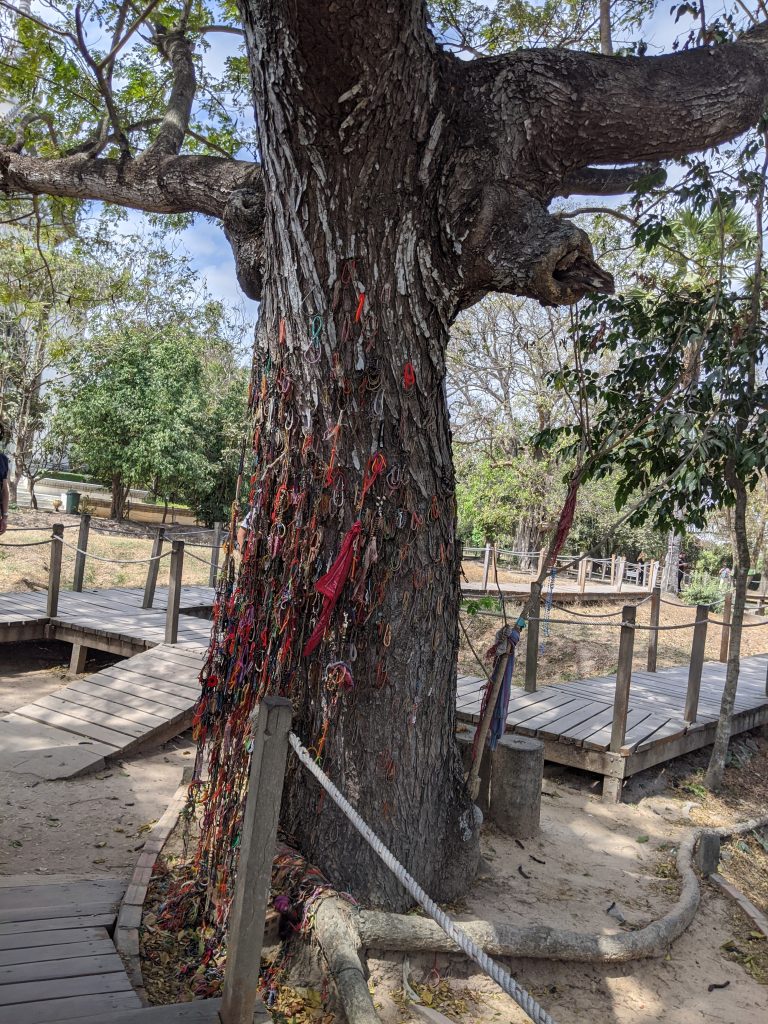

Bullets were a commodity, so to carry out these killings, people were murdered in horrendous ways, some poisoned, some stabbed, some bludgeoned. Perhaps the most horrifying is that if an adult was considered an enemy of the state, often their families and children were as well. Small children and infants were killed by having their heads smashed against Chankiri trees.

The Choeung Ek memorial park is just outside of Phnom Penh. Many of the mass graves here have not yet been excavated and are quite shallow, so it isn’t uncommon to see bits of clothing and bone sticking out of the ground, especially after heavy rain/wind. This location is best known for its large stupa, a Buddhist memorial with glass boxes filled on all sides with the skulls of five thousand victims. When the doors are opened, you can clearly see the skulls, many of which have been shattered or caved in.

Many of the bodies at Choeung Ek were murdered prisoners of the S-21 Prison, now the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, which made it my next stop. The S-21 Prison was a former secondary school transformed into a prison/torture chamber where prisoners were cruelly interrogated and tortured before being exterminated.

Prisoners would spend a few months in the prison, many facing interrogation. This included beatings, electrocution, suffocation, ripping out fingernails, waterboarding, sleep deprivation, starvation, general neglect, and rape, although if an interrogator was found out to have sexually abused a prisoner, they too would be executed. The ‘confessions’ were almost always false, with the victims telling the interrogators whatever they wanted to hear. This often included some sort of collusion with the CIA, KGB, or Vietnam.

Most foreigners had left before the genocide started, but those who remained were executed. I read a story about a New Zealand man and his friend who were out boating when they accidentally drifted into Cambodian waters. They were picked up by a Khmer Rouge patrol boat, sent to S-21 where they were tortured for several months before being executed. There are many other stories similar to this, of people just being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Some of the rooms in the memorial have been left just as they were when the Khmer Rouge left. Some contain photos of the many victims who passed through the prison. There are a number of real photos as well as paintings that showcase some of the torture and horrors that occurred in the interrogation rooms.

This was one of the most mentally exhausting days of my trip. I don’t know what I was expecting from Phnom Penh but…it wasn’t this. I’m glad I went as it was an important experience, but I felt like I was living through a horror film, and the things that happened here were as cruel as they were senseless.

Perhaps what’s most frustrating for me about all I’d seen was the lack of justice for the victims. When Germany lost World War II, Nazis were arrested and prosecuted, swasticas outlawed, reparations paid, and history books updated to denounce the horrors of the Holocaust. It doesn’t compare to the lives lost, but it’s something. It can offer some sort of closure, or justice, or a path forward. It doesn’t seem that any of this exists here. Pol-Pot was chased out of power by the Vietnamese in 1979, but the Khmer Rouge continued to have the support of China and the United States. Pol-Pot lived until 1998 where, at the age of seventy-two, he died of heart failure. A tribunal wasn’t established by the UN until 2006, and many of those responsible by that point were well into their 80s or dead. As a result, only a handful of Khmer Rouge have been tried and convicted. Just as there seems to be no real meaning to the deaths of over two million people, there is also no closure.

So sad. No country is immune to a genocide. I wish we could learn from these atrocities and stop making the same mistakes over and over.